- camel

-

—camellike, adj./kam"euhl/, n.1. either of two large, humped, ruminant quadrupeds of the genus Camelus, of the Old World. Cf. Bactrian camel, dromedary.2. a color ranging from yellowish tan to yellowish brown.4. Naut.a. Also called pontoon. a float for lifting a deeply laden vessel sufficiently to allow it to cross an area of shallow water.b. a float serving as a fender between a vessel and a pier or the like.c. caisson (def. 3a).[bef. 950; ME, OE < L camelus < Gk kámelos < Sem; cf. Heb gamal]

* * *

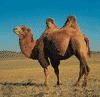

Either of two species of large, hump-backed ruminants of the family Camelidae.Camels are used as draft and saddle animals in desert regions of Africa, Arabia, and Asia. Adaptations to windblown deserts include double rows of eyelashes, the ability to close the nostrils, and wide-spreading soft feet. They also can tolerate dehydration and high body temperatures. They are thus able to go several days without drinking water. Though docile when properly trained, camels can be dangerous. The Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus) is about 7 ft (2 m) tall at the top of the two humps; the Arabian camel (C. dromedarius), or dromedary, has one hump and is 7 ft (2 m) high at the shoulder. When food is available, camels store fat in their humps to be used later for sustenance; water is produced as a by-product of fat metabolism. The feral camels of Australia were introduced to that continent in the 1800s. Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus)© George HoltonThe National Audubon Society Collection/Photo Researchers

Bactrian camel (Camelus bactrianus)© George HoltonThe National Audubon Society Collection/Photo Researchers* * *

▪ mammalIntroductioneither of two species of large ruminating hoofed mammals (mammal) of arid Africa and Asia known for their ability to go for long periods without drinking. The Arabian camel, or dromedary (Camelus dromedarius), has one back hump; the Bactrian camel (C. bactrianus) has two.These “ships of the desert” have long been valued as pack or saddle animals, and they are also exploited for milk, meat, wool, and hides. The dromedary was domesticated c. 2000–1300 BC in Arabia, the Bactrian camel by 2500 BC in northern Iran and northeast Afghanistan. Most of today's 13 million domesticated dromedaries are in India and the Horn of Africa. Wild dromedaries are extinct, although there is a large feral population in interior Australia descended from pack animals imported in the 19th century. About one million domesticated Bactrian camels live from the Middle East to China and Mongolia. Wild Bactrian camels are endangered. The largest population—1,000—lives in the Gobi Desert (Gobi).Natural historyCamels have an unmistakable silhouette, with their humped back, short tail, long slim legs, and long neck that dips downward and rises to a small narrow head. The upper lip is split into two sections that move independently. Both species are about 3 metres (10 feet) long and 2 metres high at the hump (itself 20 cm [8 inches]). Males weigh 400 to 650 kg (900 to 1,400 pounds); the female is about 10 percent smaller. Colour is usually light brown but can be grayish. Domesticated Bactrian camels are darker, stockier, and woollier than the wild form. Heavy eyelashes protect eyes from blowing sand, and the nostrils can be squeezed shut. The dromedary has horny pads on the chest and knees that protect it from searing desert sand when it lies down; the Bactrian camel lacks these callosities. Camels are generally docile, but they will bite or kick when annoyed. When excited, camels huff so sharply that spit is incidentally expelled.Camels do not walk on their hoofs. Weight is borne on the conjoined pads of the third and fourth toes; the other toes have been lost. Dromedaries have a soft, wide-spreading pad for walking on sand; Bactrian camels have a firmer foot. Like the giraffe's, the camel's gait is a pace, with both legs on a side moving together. Short bursts of 65 km (40 miles) per hour are possible, but camels are excellent plodders. Bactrian camels can carry more than 200 kg for 50 km in a day, while the more lightly built dromedaries can carry up to 100 kg for 60 km if they are worked in the coolness of night.During catastrophic droughts, herdsmen may lose all of their cattle, sheep, and goats, while 80 percent of the camels will survive, owing to the camel's ability to conserve water and tolerate dehydration. In severe heat a camel survives four to seven days without drinking, but it can go 10 months without drinking at all if it is not working and the forage contains enough moisture. Even salty water can be tolerated, and between drinks it forages far from oases (oasis) to find food unavailable to other livestock. The body rehydrates within minutes of a long drink, absorbing over 100 litres (25 gallons) in 5–10 minutes. Cattle could not tolerate such a sudden dilution of the blood because their red blood cells would burst under the osmotic (osmosis) stress; camel erythrocyte membranes are viscous, which permits swelling. A thirsty camel can reduce urine output to one-fifth normal volume and produce feces dry enough that herders use it as fuel for fires. Another adaptation is minimization of sweating. The fine woolly coat insulates the body, reducing heat gain. The camel also can allow its body temperature to rise to 41 °C (106 °F) before sweating at all. This reduces the temperature difference between the camel and its environment and thereby reduces heat gain and water loss by as much as two-thirds. Only in the hottest weather must the camel sweat. It tolerates extreme dehydration and can lose up to 25–30 percent of its body weight—twice what would be fatal for most mammals.Camels have also adapted to desert conditions by being able to endure protein deficiency and eat items other livestock avoid, such as thorns, dry leaves, and saltbush. When food is plentiful, camels “overeat,” storing fat in one area on the back and forming a hump. When the fat is depleted, the hump sags to the side or disappears. Storing fat in one place also increases the body's ability to dissipate heat everywhere else.When not corralled, camels form stable groups of females accompanied by one mature male. Females breed by three to four years of age; males begin to manufacture sperm at age three but do not compete for females until they are six to eight years old. Males compete for dominance by circling each other with the head held low and biting the feet or head of the opponent and attempting to topple it. After one camel withdraws from the bout, the winner may roll and rub secretions onto the ground from a gland on the back of its head. The dominant male breeds with all the females in each stable group. After a gestation of 13 or 14 months, one calf weighing up to 37 kg (81 pounds) is born, usually during the rainy season. Milk yields of 35 kg per day are achieved in some breeds (e.g., the “milch dromedary” of Pakistan), though normal yield is about 4 kg per day. Pastoralists typically divert most milk to their own use during the calf's first 9 to 11 months, then force weaning and take the rest. The calf is otherwise suckled 12 to 18 months. Females and males reproduce until about 20 years old. Longevity is 40 years.Camels are classified in the family Camelidae, which first appeared in North America 40 million years ago. South American camelids are the llama, alpaca, guanaco, and vicuña. The genera Camelus and Lama diverged 11 million years ago. By 2 million years ago (the late Pliocene Epoch), Camelus representatives had crossed back to Asia and were present in Africa ( Tanzania). During the Pleistocene Epoch (1,800,000 to 10,000 years ago), camelids reached South America; North American camelid stock became extinct 10,000 years ago. The family Camelidae belongs to the order Artiodactyla, a large group of hoofed mammals.Lory Herbison & George W. FrameCultural significanceCamels are among those few creatures with which humans have forged a special bond of dependence and affinity. Traditional lifestyles in many regions of the Middle East, North Africa, and Central Asia would never have developed without the camel, around which entire cultures have come into being. This camel-based culture is best exemplified by the Bedouin of the Arabian Peninsula—the native habitat of the dromedary—whose entire traditional economy depended on the produce of the camel. Camel's milk and flesh were staples of the Bedouin diet, and its hair yielded cloth for shelter and clothing; its endurance as a beast of burden and as a mount enabled the Bedouin to range far into the desert. The mobility and freedom that the camel afforded to desert Arabs helped forge their independent culture and their strong sense of self-reliance, and they celebrated the camel in their native poetic verse, the qaṣīdah (qasida), in which the nāqah (female camel) was a faithful, unwavering mount. Among these nomadic people, a man's wealth was measured not only by the number of camels he possessed but also by their speed, stamina, and endurance.Until modern times, the camel was the backbone of the caravan trade, a central pillar of the economy in large parts of Asia and Africa. In settled regions, the caravansary, located on the outskirts of most urban centres, served as a hub for business and as a source of information about the outside world for the city's residents. In the central Islamic lands, it likewise set the scene for many tales in the rich Arab-Persian oral tradition of storytelling, such as those found in The Thousand and One Nights (Thousand and One Nights, The). In Central Asia, vast and numerous camel caravans ensured the wealth and growth of the great trading cities of the Silk Road, upon which goods moved between Asia and Europe.Today the camel remains an important part of some local economies, although it has been surpassed by automated forms of transportation for most tasks. Camels are still bred for their meat, milk, and hair, and, beginning in the late 20th century, the age-old sport of camel racing was revived, particularly in the countries of the Arabian Peninsula but also as far afield as Australia and the United States.Ed.Additional ReadingHilde Gauthier-Pilters and Anne Innis Dagg, The Camel, Its Evolution, Ecology, Behavior and Relationship to Man (1981); and R.T. Wilson, The Camel (1984), provide overviews of the natural history and domestication of camels. Richard W. Bulliet, The Camel and the Wheel (1975, reprinted 1990), explains in biological and sociological context the critical role that camels played in Muslim conquests of the 7th century.* * *

Universalium. 2010.